Abstract: Understanding about aberrant behaviours has varied across time, geography and culture. In recent decades, Global Mental Health has emerged as an area of research, study and practice that is concerned with promoting equitable access to mental health services in low-resource settings. This article reflects on the emergence and development of Global Mental Health activity. The article discusses a number of contentious debates relating to Global Mental Health. Specific issues discussed include: the legitimacy given to particular forms of evidence, the primacy given to local vs. global influences, and decisions about what constitutes ‘treatment’ for emotional distress. Rather than being a monolithic enterprise, Global Mental Health is presented as a heterogeneous range of practice and research-based activities that defy easy categorisation. In particular, the innovative work that is being undertaking under the auspices of Global Mental Health to develop/evaluate psychosocial interventions, and to utilise creative/innovative ways to overcome a lack of highly trained specialists in low resource settings, offer promise for improving the lives of many people across the world.

This is an abridged and updated version of the following chapter: ‘White, R. G., Orr, D. M., Read, U. M., & Jain, S. (2017). Situating Global Mental Health: Sociocultural Perspectives. In The Palgrave Handbook of Sociocultural Perspectives on Global Mental Health (pp. 1-27). Palgrave Macmillan UK’ reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1057/978-1-137-39510-8

Introduction

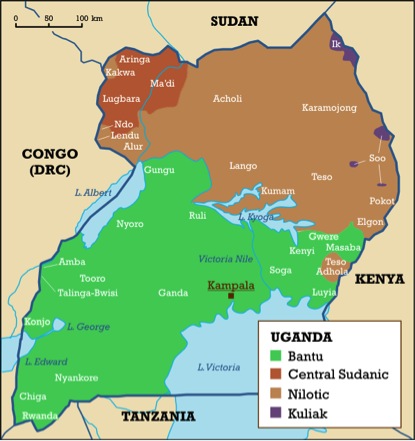

Contemporary discourses about ‘mental disorders’ owe much to the emergence of ‘Psychiatry’ as a field of medicine. The early development of psychiatry centered on the contribution of (almost exclusively male and white) protagonists based in Europe (e.g. Freud, Bleuler, Jung). As such, psychiatric theory and practice were strongly influenced by European societal attitudes and sensibilities. However, as psychiatrists began to travel to other parts of the world, interest grew in the potential applications that psychiatry might have in different cultural settings. An example of this came in 1904 when the German Psychiatrist Emile Kraepelin visited Java to determine whether the diagnosis of ‘dementia praecox’ (a fore-runner of what was to become the diagnosis of schizophrenia) existed there. In 1925, Kraepelin compared the presentation of Native American, African American and Latin American people in psychiatric institutions in the US, Mexico and Cuba (Jilek, 1995).

Questions regarding the incidence of mental disorders in different societies and the universality of psychiatric diagnoses have continued since Kraepelin’s work in the early 20th Century CE. Large-scale international comparative epidemiological studies only began during the 1960s with the World Health Organization (WHO) sponsored epidemiological studies of schizophrenia (Lovell, 2014). To this day, many countries lack nationally representative epidemiological data for mental disorders (Baxter et al., 2013). The provision of psychiatric treatment as a part of state-sponsored health care systems has also emerged unevenly, with the bulk of investment, and innovations in forms of intervention and organization, taking place in high-income countries (as classified by the World Bank). When health care systems were introduced by colonial governments in the 19th and 20th Centuries CE, mental health was a very low priority compared to public health and the control of infectious diseases (Njenga, 2002).

Despite the limited global reach of epidemiological studies and priority given to mental health, a growing field of enquiry and practice emerged in the post-colonial period, which came to be termed ‘transcultural psychiatry’. Though this was and remains a diverse field, two notable aspects were the interests that certain anthropologists had in cultural influences on mental disorders and societal responses, and the emergence of psychiatrists originating from the Global South who were trained in Europe and were attempting to apply psychiatric diagnoses to local populations. This confluence of anthropologists and psychiatrists, some of whom had been trained in both disciplines, was strengthened after the 1950s by the beginning of large-scale migration from the former colonies to countries of Europe and North America and the growing numbers of service users from diverse cultures in psychiatric services. Academic departments and courses in transcultural psychiatry began to be established, notably at McGill in Canada and Harvard in the US, and academic journals such as Transcultural Psychiatry began publication. In 1995, some of the most influential anthropologists in transcultural psychiatry based at Harvard University, including Arthur Kleinman, published a book entitled World Mental Health: Problems and Priorities in Low-Income Countries (Desjarlais et al., 1995). This volume set out the concerns regarding human rights, lack of treatment and rising incidence of mental disorders in terms that in many ways set the agenda for what was later to be termed ‘Global Mental Health’. Six years later the World Health Organization brought renewed attention to mental health by making it the topic of their annual ‘World Health Report’ for the first time in its history (WHO, 2001).

The term ‘Global Mental Health’ (GMH) was first coined in 2001 by the then US Surgeon General, David Satcher. Reflecting on the publication of the 2001 World Health Report (WHO, 2001) and a year-long campaign by the World Health Organization (WHO) on mental health, Satcher proposed that the United States should bring mental health onto the global health agenda by ‘taking a leadership role that emphasizes partnership, mutual respect, and a shared vision of improving the lives of people who have mental illness and improving the mental health system for everyone’ (2001, p.1697). GMH was given additional visibility through the launch of the Movement for Global Mental Health (MGMH). The MGMH traces its origins back to the consortium of experts that constituted The Lancet Group for Global Mental Health (2007; 2011), and who published two series of papers to highlight the need for action to build capacity for mental health services in low- and middle-income countries. The MGMH now has a membership of around 200 institutions and 10,000 individuals (http://www.globalmentalhealth.org/about). The MGMH was a partner in The Lancet Commission for Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development (Patel et al., 2018) which was launched On World Mental Health Day, 10th October 2018. The launch of the commission coincided with a Global Ministerial Mental Health Summit in London, UK (https://globalmhsummit.com/home). The central message conveyed by the commission, and indeed the principal focus of the summit, was that mental health and wellbeing are fundamental to the achieving sustainable development goals (UN, 2015).

This article briefly summarises some key debates concerning GMH: including contention about the legitimacy given to particular forms of evidence, the primacy given to local vs. global influences, and assumptions regarding what constitutes ‘treatment’ for emotional distress.

Standardisation and Evidence-based Medicine

Since its emergence, GMH has been the target of a vocal critique, most prominently concerning a perceived dominance of biomedical approaches. Critics have suggested that GMH is a neo-colonial, medical imperialist approach that serves to expand markets for psychotropic medication (Summerfield, 2012; Mills, 2014). Refuting such accusations, Patel (2014) points out that the bulk of interventions evaluated in GMH research have focused on psychosocial interventions. Furthermore, Patel (2014, p.786) states that it would be ‘unethical to withhold what biomedicine has to offer, simply because it was ‘invented somewhere else’.’ Bemme and D’Souza (2014) have contended that the globalization of particular forms of intervention has not been a principal concern of GMH. Instead, they suggest that a central feature of GMH has been the dissemination and utilization of particular epistemologies and research methodologies for evaluating interventions across the globe. The emergence of the Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) paradigm (see Guyatt et al., 1995), and the hierarchical approach to research evidence that it espouses, has had a significant impact on shaping standardized procedures for evaluating health interventions.

Thomas et al. (2007) have cautioned against the assumption that human behaviours and problems are amenable to investigation using the same positivist methods that are applied in the natural sciences. In a similar vein, EBM has also been criticized for disregarding the social nature of science and obscuring subjective elements of the human interactions that occur in the context of medicine (Goldenberg, 2006). Greenhalgh et al. (2014) identified a number of limitations in the EBM paradigm as currently practiced, including a susceptibility to bias in trials, a failure to take account of multi-morbidity, and a tendency to promote over-reliance on ‘algorithmic rules’ over reasoning and judgment. Furthermore, other commentators have suggested that ‘gold standard’ EBM methodologies may lack sufficient sophistication for understanding cross-cultural nuances in how emotional distress can be understood and addressed in different contexts (Summerfield, 2008; Kirmayer & Pedersen, 2014).

Kirmayer and Swartz (2013) highlighted the need for the GMH agenda to embrace a ‘pluralistic view of knowledge’, which can be integrated into empirical paradigms guiding GMH-related research. More recently, the notion of mental health interventions as ‘complex’ interventions interacting with context to influence outcomes has led to a challenge to the gold standard of randomized controlled studies (Moore et al., 2015). Researchers have called for new methods of evaluation including the use of qualitative methodologies such as ethnography to observe such interactions and unintended effects (Kirmayer & Pedersen, 2014). These approaches have been embraced in several studies of community-based mental health interventions in low-income settings across the globe (de Silva et al., 2015). The development of GMH has helped to build an appreciation that the experience of emotional distress is embedded within the particularities of social and moral worlds, and calls for methods of investigation and evaluation which are sensitive to ‘locally relevant evidence’ and take account of contextually situated experience (Kienzler and Locke, 2017).

The ‘Global vs. Local’ Distinction

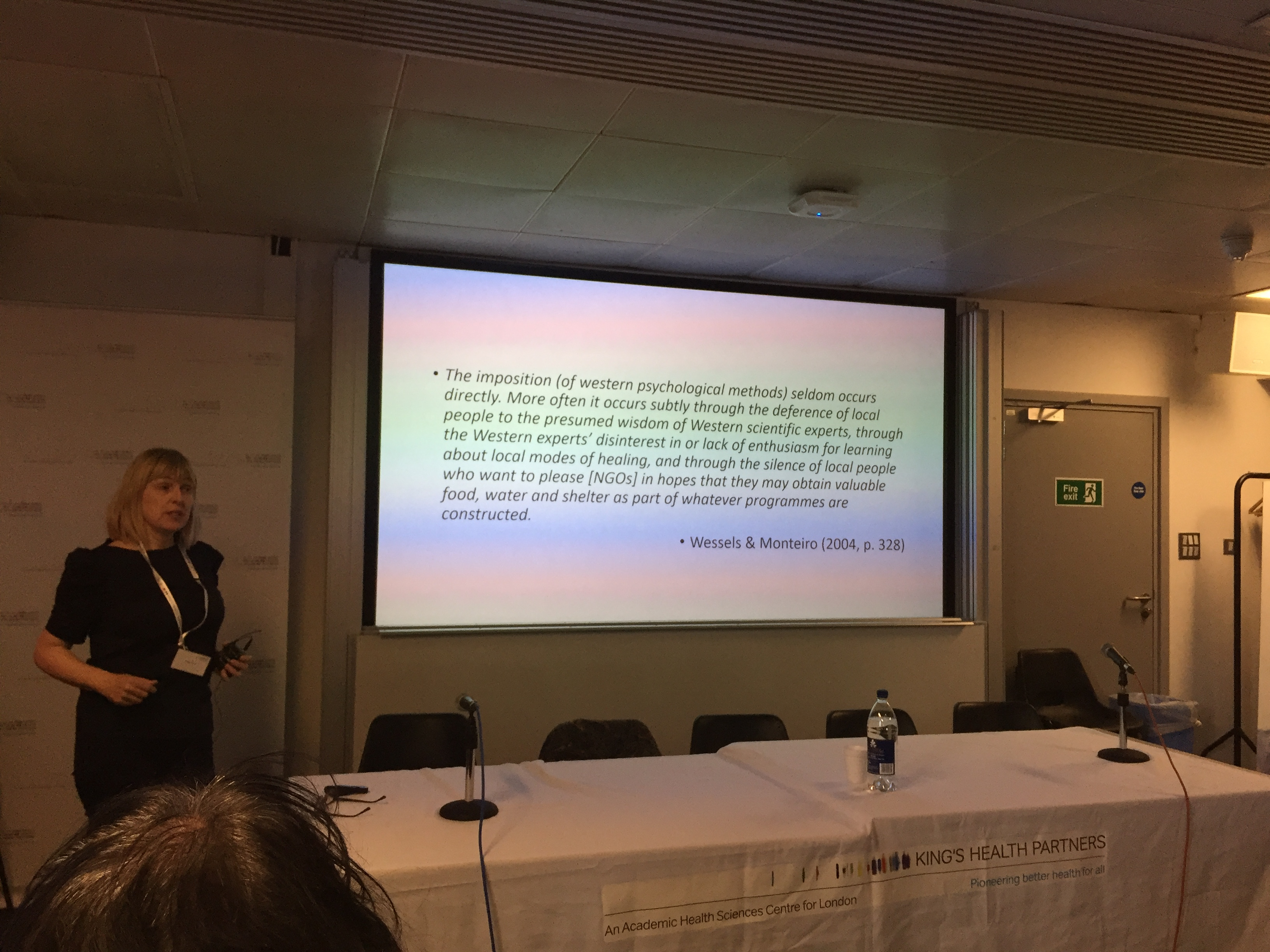

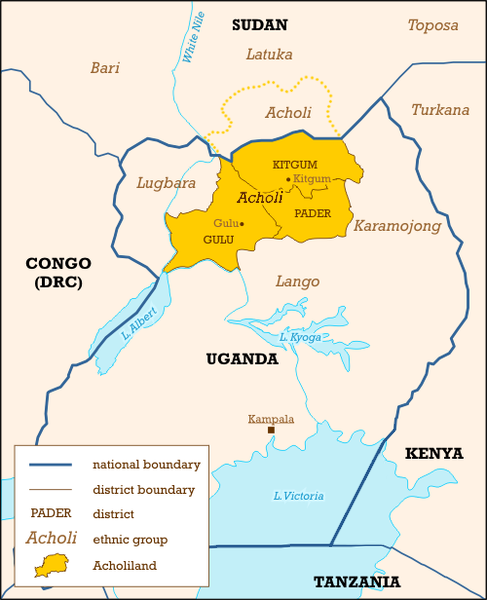

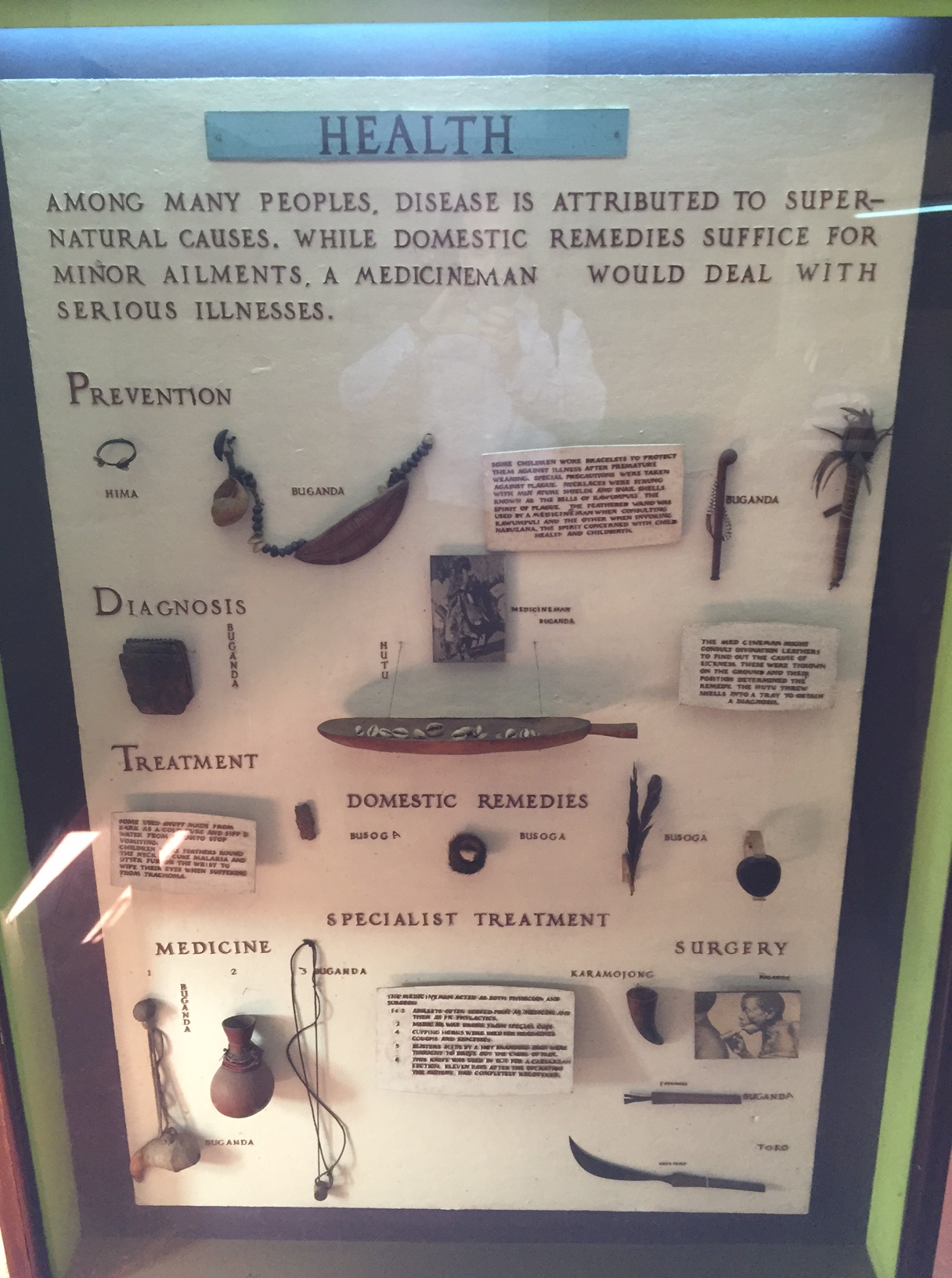

The dichotomy that has been drawn between forms of support that reflect ‘local’ (i.e. specific to particular contexts) beliefs and practices, as opposed to ‘global’ (i.e. standardized/universalist) approaches, has been keenly debated in GMH-related discourses. Some have argued that global initiatives for mental health pose a threat to indigenous or local practices (Mills, 2014; Fernando, 2014). Patel (2014) has warned against the idealization of indigenous (i.e. local) practices, which can include inhumane treatments and practices. Miller (2014) has also argued that a person living in a LMIC ‘deserves better than being urged to stay in (his/)her niche in some great cabinet of ethnopsychiatric curiosities’ (p.134). Bauman (1998) highlighted the way in which what is considered to be ‘local’ has become organic and porous, as new and ever-evolving associations are formed with ‘global’ processes. Bemme and D’Souza (2014) pointed to the relevance of the anthropologist Anna Tsing’s (2005) concept of ‘friction’ for exploring the connections between the ‘local’ and ‘global’ in the context of GMH. Friction captures how the supposedly smooth flows of ‘universal’ ideas, concepts and policies across the globe are, in reality, slowed down or dragged back on particular terrains; yet at the same time, movement only occurs in the first place through the friction that results from gaining purchase on a particular ground. Thus, the global and the local may hinder each other and/or propel each other forward, but they are never locked into the kind of zero-sum rivalry with which they are so often portrayed. Tsing’s approach emphasises the ongoing co-production of culture in the encounter between universal and particular in ‘zones of awkward engagement’ (Tsing 2005, p.4, xi); rather than being opposites, the two are mutually altered in unforeseen ways by this process. The dynamic interaction between ‘local’ and ‘global’ has been captured by the hybrid concept referred to as ‘glocalization’ (Robertson, 1994), which recognizes the process of syncretization that occurs between local and more global influences. From this perspective, ‘doing’ GMH would cease to be a debate between the relative merits of adopting universal categories or preserving a pre-existing set of local categories, and would become a question of what further possibilities might emerge from the meeting between the two. So, whilst facilitating opportunities to recognise the importance of ‘local’ context, GMH research, practice and study also needs to be mindful of the way in which local experience is influenced by wider social, political and economic forces, and the contribution that structural factors (including poverty, war and violence, migration and displacement) make to mental health.

The ‘Treatment Gap’ and Community-based Interventions

Borrowing language from Global Health (GH), The Lancet Series on Global Mental Health (2007; 2011) and the mhGAP Action Programme (WHO, 2008) and mhGAP Intervention Guide (WHO, 2010; 2016) draw on the notion of the need to fill the ‘treatment gap’ (i.e. the gap between what the numbers of people assumed to be suffering from mental illness and the numbers receiving treatment). As is the case for burdensome physical health conditions (such as HIV/AIDS and malaria), the urgency for ‘scaling-up’ services for mental health difficulties has in part been justified on the basis of the moral obligation to act (Patel, Saraceno & Kleinman, 2006; Kleinman, 2009). Indeed, the MGMH has been engaged in concerted efforts to mobilize stakeholders and lobby for policy change to address the ‘treatment gap’. Vikram Patel has stated that there is a need ‘to shock governments into action’ and that language should be employed strategically for this purpose (Bemme & D’Souza, 2012; para. 24). For example, it is suggested that the ‘treatment gap’ for mental health difficulties is as high as 85% in low-income countries (Demyttenaere et al., 2004), and that urgent action needs to be taken to bridge it. However, the aforementioned concerns about the poor quality of epidemiological data relating to mental disorders in LMIC (see Baxter et al., 2013) will have important implications for the accuracy of estimates of the ‘treatment gap’.

Critics have argued that the concept of the ‘treatment gap’ has privileged particular forms of treatment whilst simultaneously failing to recognize the important contribution that other forms of support and healing may bring to people living across the globe (Bartlett et al. 2014; Fernando, 2014). In particular, allopathic forms of intervention have assumed high levels of credibility and legitimacy in the Global North and elsewhere. The term ‘allopathy’ was first introduced by German physician Samuel Hahnemann (1755-1843) when he conjoined the Greek words ‘allos’ (opposite) and ‘pathos’ (suffering). It is defined as the treatment of disease by ‘conventional’ means (i.e. with drugs having effects opposite to the symptoms). Commentators have expressed concerns that employing rhetorical language of the ‘treatment gap’ may well shock governments into taking action, but this action may not be inclusive of the pluralistic forms of support available (White & Sashidharan, 2014a,b). Researchers have suggested that pluralism and a multiplicity of treatment options might bring potential benefits for engagement and outcome for individuals experiencing mental health difficulties in LMIC (Orr and Bindi, 2017). Jansen et al. (2015) pointed out that the concept of the ‘treatment gap’ has advocated a particularly individualistic approach to scaling-up services for mental health in LMIC. Similarly, Kohrt & Griffith (2015) have highlighted the need for practitioners to work across therapeutic levels (including family, community, and wider contexts) according to ecological systems theory. Fernando (2012) suggested that the burden of mental health problems experienced collectively by communities is likely to be greater than the sum of the burden on the individual members of that community, especially in the context of ‘collective traumas’ (see Audergon, 2004; Somasundaram, 2007; 2010). Bemme and D’Souza (2014) observed that GMH initiatives have narrowly conceptualized ‘community’ as a method of service delivery. Specifically, community care is proposed as more cost-effective option (Das & Rao, 2012).

Moving forward, there is a need to explore how the concept of ‘community’ can be promoted as a means of harnessing collective strengths and resources to promote mental wellbeing (Jansen et al., 2015). In particular, community-based psychosocial interventions may offer promise for alleviating the burden of emotional distress. Psychosocial interventions are based on an appreciation that aspects of a person’s surrounding social environment can combine with psychological factors to impact on their physical and mental health. The Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Network (MHPSS Network – https://mphss.net) provides examples of innovative approaches for addressing psychological and social determinants of mental health. It is important that community-based approaches are cognisant of concerns that community action and volunteering in GH and GMH initiatives may take advantage of community workers by relying heavily on their often unpaid and demanding work (Maes, 2015; Kalofonos 2015). This has implications for both the sustainability and quality of care provided, particularly where there is inadequate investment in ongoing training and supervision.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Over the last 18 years, GMH has evolved from its embryonic roots to establish itself as a field of study, debate and action, which is now latticed by diverse disciplinary, cultural and personal perspectives. Whilst the development of GMH has attracted contention and controversy, this contention has tended to be based around narrow and restrictive interpretations of GMH. Rather than being a monolithic endeavour, GMH needs to be understood as a heterogeneous endeavour incorporating a diverse range of activities. Moving forward it will be important to recognise the important opportunities that GMH provides to work collaboratively with local stakeholders to generate innovate, pragmatic, and culturally sensitive approaches to addressing mental health and wellbeing in low resource settings.

Biographical Notes About Authors

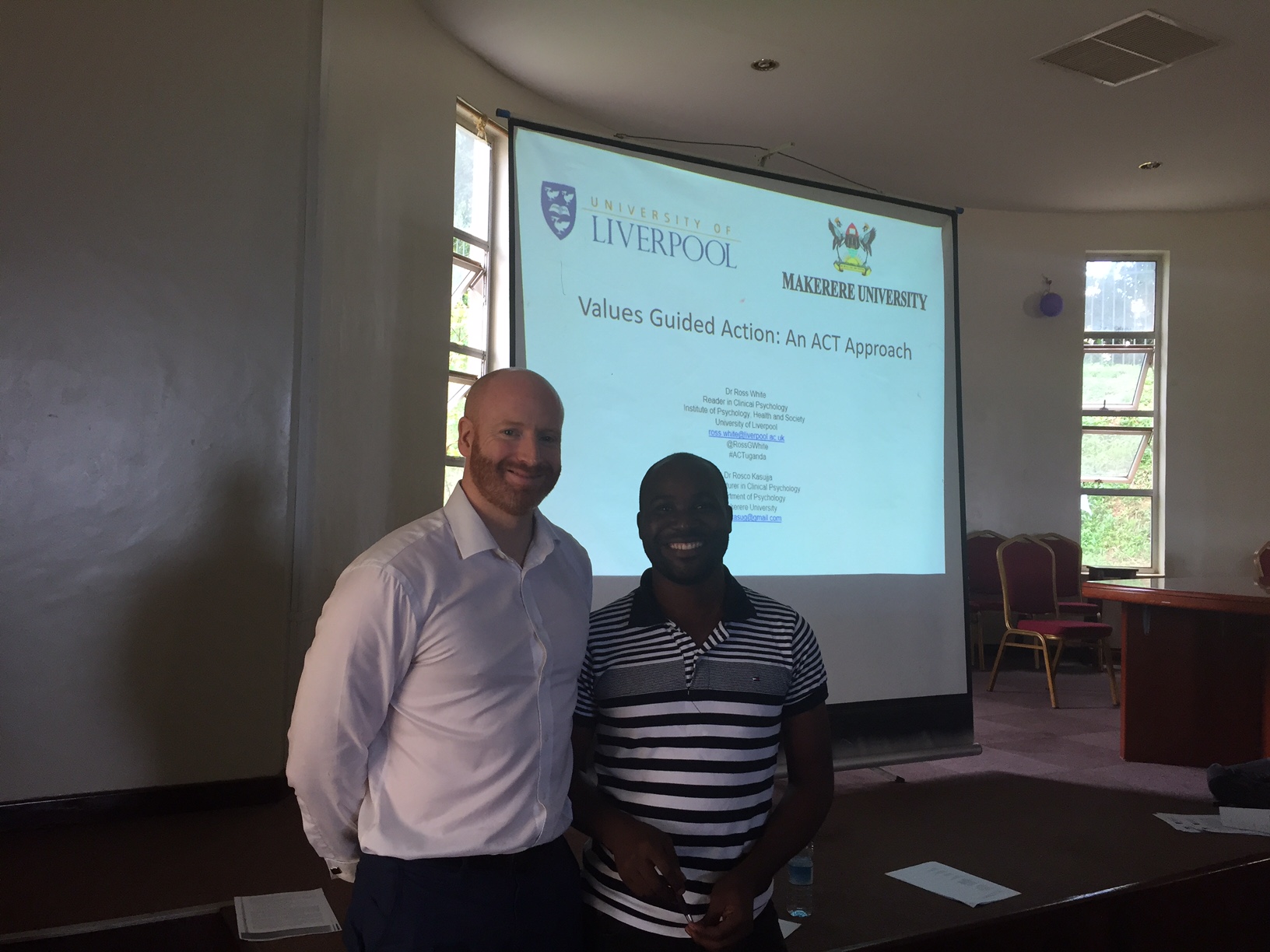

Dr Ross White is an Associate Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Liverpool. His research collaborations with the World Health Organization and United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees focuses on evaluating psychosocial interventions for refugees in the UK, EU and sub-Saharan Africa. Dr David M. R. Orr is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Social Work, Wellbeing and Social Care at the University of Sussex. His research projects have focused on adult safeguarding and self-neglect, global mental health, and representations of dementia in contemporary films and fiction. Dr Ursula M. Read is an anthropologist and research fellow based in Global Health and Social Medicine at King’s College London. Her research utilises ethnographic methods to explore the experiences of people with severe mental illness and their families in Ghana. Dr Sumeet Jain is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Edinburgh. His research draws on inter-disciplinary knowledge and mixed methods to unpack the notion of a ‘global’ mental health, and attempts to inform development of services that account for local experiences and understandings of psychological distress.

References

Audergon, A. (2004). Collective trauma: the nightmare of history. Psychotherapy and Politics International, 2(1), 16-31.

Bartlett, N., Garriott, W., & Raikhel, E. (2014). What’s in the ‘Treatment Gap’? Ethnographic Perspectives on Addiction and Global Mental Health from China, Russia, and the United States. Medical Anthropology, 33(6), 457-477.

Bauman, Z. (1998). Globalization: The human consequences. New York: Columbia University Press.

Baxter, A. J., PaOon, G., ScoO, K. M., Degenhardt, L., & Whiteford, H. A. (2013). Global epidemiology of mental disorders: what are we missing. PLoS One, 8(6), e65514.

Bemme D, D’Souza. N. Global Mental Health and its discontents. 2012. http://somatosphere.net/2012/07/global-mental-health-and-its-discontents.html. Accessed 31st December 2018.

Bemme, D., & D’Souza, N. A. (2014). Global mental health and its discontents: An inquiry into the making of global and local scale. Transcultural Psychiatry, 51(6), 850-874.

Das, A., & Rao, M. (2012). Universal mental health: Re-evaluating the call for global mental health. Critical Public Health, 23, 1-7.

Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al. (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA, 291: 2581–2590.

De Silva, M. J., Rathod, S. D., Hanlon, C., Breuer, E., Chisholm, D., Fekadu, A., … & Medhin, G. (2015). Evaluation of district mental healthcare plans: the PRIME consortium methodology. The British Journal of Psychiatry, bjp-bp.

Desjarlais, R. et al. (1995). World mental health: Problems and priorities in lowincome countries. New York Oxford University Press.

Fernando S. (2014). Globalization of psychiatry: A barrier to mental health development. International Review of Psychiatry, 26, 551–57

Fernando, G. A. (2012). The roads less traveled: Mapping some pathways on the global mental health research roadmap. Transcultural Psychiatry, 49, 396-417.

Goldenberg, M. (2006) On evidence and evidence-based medicine: lessons from the philosophy of science.Social Science & Medicine 62: 2621-2632.

Greenhalgh, T., Howick, J. & Maskrey, N. (2014) Evidence-based medicine: a movement in crisis? British Medical Journal, 348, g3725

Guyatt, G. H., Sackett, D. L., Sinclair, J. C., Hayward, R., Cook, D. J., Cook, R. J., … & Wilson, M. (1995). Users’ guides to the medical literature: IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. Journal of the American Medical Association, 274(22), 1800-1804.

Jansen, S., White, R., Hogwood, J., Jansen, A., Gishoma, D., Mukamana, D., & Richters, A. (2015). The “treatment gap” in global mental health reconsidered: Sociotherapy for collective trauma in Rwanda. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6, doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v6.28706.

Jilek WG. (1995). Emil Kraepelin and comparative sociocultural psychiatry. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Nueroscience, 245, 231–38.

Kalofonos, I. (2015) “We can’t find this spirit of help”: Mental health, social issues and community home-based care providers in central Mozambique. In Kohrt, B.A. & Mendenhall, E. (eds.) Global Mental Health: Anthropological Perspectives. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press. Pp. 309-323.

Kienzler, H., & Locke, P. (2017). The effects of societal violence in war and post-war contexts. In The Palgrave handbook of sociocultural perspectives on global mental health (pp. 285-305). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Kirmayer, L. & Pedersen, D. (2014). Toward a new architecture for global mental health. Transcultural Psychiatry, 51, 759-76.

Kirmayer, L. J., & Swartz, L. (2013). Culture and global mental health. In V. Patel, M. Prince, A. Cohen, & H. Minas (Eds.) Global mental health: Principles and Practice (pp. 44–67). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Kohrt, B.A. & Griffiths, J.L. (2015) Global Mental Health praxis: perspectives from cultural psychiatry on research and intervention. In Kirmayer, L.J., Lemelson, R. & Cummings, C.A. (Eds.). (2015) Re-visioning Psychiatry: Cultural Phenomenology, Critical Neuroscience, and Global Mental Health. Cambridge University Press.

Lovell, A. M. (2014). The World Health Organization and the contested beginnings of psychiatric epidemiology as an international discipline: one rope, many strands. International Journal of Eepidemiology, 43 (suppl 1), i6-i18.

Kleinman, A., & Cohen, A. (1997). Psychiatry’s global challenge. Scientific American, 276(3), 86-89.

Maes, K. (2015). “Volunteers Are Not Paid Because They Are Priceless”: Community Health Worker Capacities and Values in an AIDS Treatment Intervention in Urban Ethiopia. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 29(1), 97-115.

Marmot M. (2014). Commentary: Mental health and public health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 43 (2): 293-296.

Marmot Review Team (2010). Fair Society, Healthy Lives: Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England Post-2010. London: UCL Institute of Health Equity.

Miller, G. (2014) Is the agenda for global mental health a form of cultural imperialism? Medical Humanities, 40 (2), 131-134.

Mills C. (2014). Decolonizing Global Mental Health: The psychiatrization of the majority world. London, UK: Routledge.

Njenga, F. (2002). Focus on psychiatry in East Africa. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 181(4), 354-359

Orr, D. M., & Bindi, S. (2017). Medical pluralism and global mental health. In The Palgrave Handbook of Sociocultural Perspectives on Global Mental Health (pp. 307-328). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Patel, V., Saraceno, B., & Kleinman, A. (2006). Beyond Evidence: The Moral Case for International Mental Health. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163 (9), 1312 – 1315.

Patel V. (2014) Why mental health matters to global health? Transcultural Psychiatry, 51, 777-789.

Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., … & Herrman, H. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. The Lancet, 392(10157), 1553-1598.

Robertson, R. (1994). Globalization or glocalization? Journal of International Communication, 1, 33–52.

Satcher, D. (2001). Global mental health: its time has come. JAMA, 285(13), 1697-1697.

Saxena, S., Thornicroft, G., Knapp, M., & Whiteford, H. (2007). Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. The Lancet, 370, 878–889.

Somasundaram, D. (2007). Collective trauma in northern Sri Lanka: A qualitative psycho- social ecological study. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 1, 5–31. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-1-5

Somasundaram, D. (2010). Collective trauma in the Vanni – A qualitative inquiry into the mental health of the internally displaced due to the civil war in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 4, 22–52. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-4-22.

Summerfield D. (2008). How Scientifically valid is the knowledge base of global mental health. British Medical Journal, 336: 992–94.

Thomas, P., Bracken, P., & Yasmeen, S. (2007). Explanatory models for mental illness: Limitations and dangers in a global context. PAK. J. NEUROL. SCI., 2, 176- 177.

Tsing, A. L. (2005). Friction: An ethnography of global connection. Princeton University Press.

United Nations (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. UN: New York.

White, R. G., & Sashidharan, S. P. (2014a). Towards a more nuanced global mental health. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(6), 415-417.

White, R. G., & Sashidharan, S. P. (2014b). Authors’ Reply to Cohen: A nuanced perspective? The British Journal of Psychiatry, 205, 329-330.

World Health Organization (2008). Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP): Scaling up Care for Mental, Neurological and Substance Abuse Disorders. WHO: Geneva.

World Health Organization. (2010). Mental Health Gap Intervention Guide. WHO: Geneva.

World Health Organization & Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation (2014). Social Determinants of Mental Health. Geneva: WHO.

World Health Organization. (2016). Mental Health Gap Intervention Guide 2.0. WHO: Geneva.

Conclusion

Conclusion